DIVING & EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL

Content:

EOD Operation Onboard HMS SOUTHAMPTON in 1988

Operation Blackleg 16th September 1982 – 28th January 1983

A Short History of Diving

The History of Military and Naval Diving

The Royal Navy Clearance Diving Branch

HMS Vernon and Royal Naval Reserve Diving after 1960

Links to: The History of Royal Navy Diving

Mine Warfare and Clearance Diving Branch History

More RN mine warfare and diving stories.

Royal Navy Clearance Divers - Forces TV Item

What does it take to be a Royal Navy Clearance Diver?

EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL OPERATION ONBOARD HMS SOUTHAMPTON IN 1988

In 1988, Warrant Officer (Diver) Colin “Scouse” Kidman was serving in the Fleet Diving Group, based at Portsmouth. Following a collision between HMS SOUTHAMPTON and the P&O container ship TORBAY in the Persian Gulf he was deployed to the United Arab Emirates with a Diving Unit to carry out an assessment of the Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) work required. The “assessment” developed into a 7 week EOD operation.

This dangerous operation, which necessitated meticulous planning and great care in implementation, was carried out in arduous conditions. In addition to having to operate under very hazardous circumstances, it involved work inside the ship in temperatures up to 45°C, diving in compartments flooded with sea water, hydraulic fluid and other debris with an underwater temperature of 34°C. The need to carry out engineering work, metal cutting and heavy lifting in close proximity to damaged explosive ordnance added to the risks.

HMS SOUTHAMPTON

Sea Dart missiles (red) in the launcher with the 4.5” gun just for’d. The respective magazines are directly below.

This is Colin Kidman’s report:

“On the evening of 3 September 1988 while on Armilla Patrol, HMS SOUTHAMPTON was in collision with the 34,000 ton P&0 container ship TORBAY. At 1300, 4 September 1988 the Fleet Diving Group Headquarters in Portsmouth received instructions to deploy a Unit to survey the damage in the magazines and estimate the Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) work required to make the ship safe for docking. The following personnel were nominated:

WO(D) Kidman, PO(D) Hill, LS(D)s Lynch and Johnson, AB(D)s McHugh and John.

At 0930, 5 September 1988 the Unit arrived at FUJAIRAH United Arab Emirates (UAE) where HMS SOUTHAMPTON was berthed and commenced a detailed survey.

Damage to HMS SOUTHAMPTON’s port side.

Diver surveying underwater damage. The protruding steel sections were later removed by divers.

The internal and underwater inspection of HMS SOUTHAMPTON revealed extensive damage. The bulbous bow of the TORBAY had carved through HMS SOUTHAMPTON’s Seadart missile magazine, only stopping when it met the keel. Flooding was extensive, including messdecks and the computer room, but the most significant flooding was in the Seadart and 4.5 magazines.

The inside of the magazine had been reduced to an array of broken missiles and tangled metal. The magazine raft assembly had been severely damaged and the port Seadart spray tank had been pushed into the Seadart magazine causing extreme damage to 7 of the 20 missiles embarked. The rails of the port side of the raft assembly had been pushed forward penetrating the bulkhead and entering the adjacent 4.5 magazine.

This movement had also caused the leading port missile to be driven into the forward bulkhead of the magazine. The twisted metal of the spray tank had cut the port after missile in half and entombed the boost motor under debris.

The split in the 4.5 magazine after bulkhead caused by the penetration of the port raft assembly rails, measured 2 metres across and was below the level of the deck plates. As the rails protruded from the split it was not possible to fix a temporary patch over the split.

The magazine contained a large number of live 4.5 and smaller calibre rounds. All 4.5 cased rounds appeared undamaged, some were flooded when inspected later, 4 boxes of Phalanx ammunition had been crushed and were trapped under the protruding rail assembly, beneath the deck plates.

RFA DILIGENCE arrived at FUJAIRAH early on 5 September and with her assistance the 4.5 turret and Seadart launcher were removed to reduce top weight. This caused the water level in the Seadart magazine to fall uncovering most of the missile warheads, therefore, the forepeak was flooded to bring the water level back up to keep the damaged warheads wet.

HMS MIDDLETON's diving team assisted in the lashing of the missiles to a shoring of 4 x 4 timbers, positioned in the Seadart magazine to prevent the missiles moving during the tow by RFA DILIGENCE to DUBAI.

On arrival at DUBAI, RFA DILIGENCE and HMS SOUTHAMPTON anchored off to await diplomatic clearance. During this time the ammunition stowed in the 4.5 magazine was removed to a temporary magazine, the helicopter hangar, to reduce the amount of explosive materials forward. This task took 48 hours as all ammunition had to be moved manually. HMS SOUTHAMPTON's Ships Company assisted the team in this hot and strenuous task.

The damaged boxes of Phalanx ammunition could not be removed initially as they were trapped by the rails from the Seadart magazine. After 2 hours work using a crowbar and chain hoist, the boxes were removed.

Diplomatic clearance was given to proceed to the neighbouring Emirate, ABU DHABI where preparations for the EOD phase to remove the missiles could take place. SOUTHAMPTON was allowed to berth at PORT ZAYED for 7 days where preparations to conduct the EOD task at sea commenced.

The Seadart missiles are normally embarked and disembarked through the launcher. As this was almost totally destroyed in the collision the only access was through the blow hole. It was therefore decided that the safest way to remove the missiles was by cutting 2 further blow hole size holes in 01 deck and then remove 2 deck cross passage. Before this could commence sections of the deck and deckhead fittings had be removed. The SOUTHAMPTON's ships company worked for 7 days removing equipment and delagging deckheads, at the same time the team removed the Seadart magazine deckhead fittings and produced a scale plan of the magazine showing the positions of the top and base of each missile relative to the forward bulkhead. From this the team was able to mark the missile lift positions on 2 deck.

To enable the missiles to be lifted clear of the magazine a gantry was constructed over the area of the deck where the intended holes would be cut. It was constructed by the DUBAI Transport Company (DUTCO), stood 7 metres high and had a SWL of 2 ton. Two moving travellers with low powered electric hoists were attached to the gantry and could be moved to plumb wherever they were required over the site.

HMS SOUTHAMPTON’s port side showing the locally made gantry and a temporary patch welded over the damaged area to prevent the free flow of water.

As final arrangements were being made to conduct the EOD phase at sea further negotiations with the Ruler of DUBAI took place and diplomatic clearance was given for SOUTHAMPTON to proceed to an isolated berth in the very large port of JEBEL ALI.

On 26 September, DILIGENCE arrived at 45 berth in JEBEL ALI with SOUTHAMPTON under tow. The area had been evacuated and cordoned off to 200 metres to landward and 400 metres was cleared to seaward.

A large barge was purchased and modified to hold the missiles after removal. Twenty steel containers (“coffins”) were welded to the upper deck and 10 scuttling valves were fitted. A salvage pump was also fitted to prevent the barge sinking before the appropriate time.

Steel containers (“coffins”) fitted to a barge. Each contained sand bags on which missiles rested and was flooded.

After berthing at JEBEL ALI the cutting of HMS SOUTHAMPTON’s 01 deck commenced, this was completed in one day by DUTCO using oxy-acetylene. After 3 sections had been removed from 01 deck a support beam was welded fore and aft across the centre of the holes to prevent the already weakened decks from collapsing.

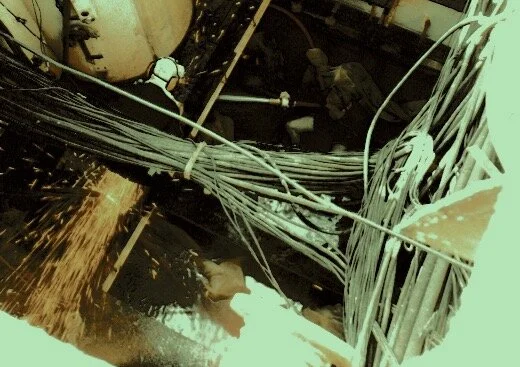

The ship's company were evacuated on the morning of 28 September and the team commenced cutting 2 deck. Due to the close proximity of the missile warheads to the underside of 2 deck, the deck cutting operation had to be conducted using hydraulic cutting discs. The In-service standard hydraulic power pack was found very suitable. Wet blankets were positioned over the warheads to protect them. As one member of the team cut the deck another member remained underneath the deck with a running fire hose, damping down to prevent any possible ignition of the many combustible fluids contaminating the sea water.

A team member cutting through the deck, another can just be seen below with a fire hose damping down to prevent fire. Had the cables in the foreground been damaged the cost of repairing SOUTHAMPTON to an operational state would have been unaffordable.

The team was limited to 30 minute work cycles because of the high ambient temperatures, combined with the contamination of hydraulic fluid and fuel oil in the water and also cutting of the longitudinal beams which had to be cut from underneath.

The deck cutting was completed in 3 days, 2 days earlier than estimated, this was achieved due to the continuous efforts of the team and the professional expertise of the Warrant Officer Chippy JOHN DENZEY who remained with the team during the whole evolution.

On completion of the deck cutting, the barge was brought alongside Starboard side of the forecastle. An earthing cable joined the barge to the ship to prevent any RADHAZ problems. The decks around the magazine were covered with shock mats and fire fighting equipment was checked. The preparations were now complete.

After an individual survey of each missile the plan was to:

a. Remove the wings off each missile, to assist stropping. Cut away each trolley cover to gain access for stropping.

b. Remove the easiest of the missiles first by stropping them with the specially designed strops.

On 2 October the first missile was stropped in the following manner:

a. Two 12 metre braided nylon strops were passed around the base of the boost motor and butt hitched twice up the length of the missile body. Five mechanical strops were then secured around the missile body spaced at one metre intervals. After the slack had been taken up on the low powered electric winch the 4 missile unlatching mechanisms were operated, releasing the 4 locking bolts. The missile was then hoisted clear of the trolley approximately 2 metres. At this point the hoist was stopped and the 4 flip out fins were removed, a further 2 mechanical strops were secured to the boost motor and the missile was then hoisted clear of the water to drain.

A Seadart missile being lifted on strops.

This stropping method was devised to prevent the boost motor from breaking away at the launch beam; the weakest point, as the representatives of SINO had advised that if the boost motor dropped onto the deck it would probably ignite. (Apparently no drop test has ever been conducted on this ordnance).

A missile, complete with boost motor, hoisted clear of the deck.

b. The missile was lifted clear of the decks and then lowered horizontally into another specially designed strop, a type of hammock strop. With the aid of a spreader bar the missile was then hoisted in the hammock strop and then lowered into one of the coffins on the barge. The coffin contained a layer of sandbags and the missile was fully immersed in water.

A missile in the hammock sling.

c. This method of removal was then used on a further 9 missiles, the stropping and transfer to the barge taking approximately 2 hours per missile.

Having established a clear area within the magazine the task of removing the more difficult missiles could commence. Missile JZ 432 had been pushed into the forward bulkhead by the impact of the collision. The team commenced cutting away the bulkhead fittings with hydraulic discs, which were entangled around the missile body. When this was completed the 8 bolts holding the launch frame to the boost motor were removed, the boost percussion link pipe and the launch electrical leads were then cut. The body of the missile was then stropped in a similar method to previous missiles and lifted clear of the magazine.

A damaged Seadart missile.

The boost motor had been crimped into the trolley by the trolley support arms bending inwards. By pushing these aside with a hydraulic ram (ENAPAC) the boost motor was stropped and hoisted clear. This task took 6 hours to complete.

One missile had been partially separated from the boost motor at the control rink. The team commenced the removal by firstly removing the launch beam securing bolts, then carefully stropping the upper section of the missile body. After cutting away the boost percussion link pipe and launch electrical leads the upper section was gently hoisted on chain hoists at the same angle. Because of the damaged separation bolts, which contained explosive detonators, the body was hoisted without putting any strain onto the separation bolts. The boost motor was stropped and lifted clear separately. This took 4 hours. A further 8 missiles were removed during the following 5 days using cutting gear and hoists.

A detached boost motor being lifted separately.

On 9 October the final task was to remove the last live boost motor remaining in the magazine. Work commenced to clear debris from around it. The main problem was that the spray tank was sitting on top of the boost motor and would have to be lifted to allow the motor to be pulled clear. Six 2 ton chain hoists were positioned in areas around the tank and wire strops were attached to the base, this enabled the tank to be hoisted only some 20 cms above the boost motor. However, this allowed a more detailed inspection of the damaged boost motor, which exposed a large area of damage where the outer casing had been split exposing the explosive filling. After 4 hours work it was decided to continue the task next day as light was failing and everyone was ready for a rest.

The next day 2 members of the team entered the water, unfortunately after 3 hours one badly gashed his leg which required 5 stitches. At midday work continued using hydraulic rams and cutting gear, but again at the close of the day the motor remained entombed. On 11 October work continued on cutting away debris, though by this time the water within the magazine was getting heavily contaminated and hydraulic fluid from the raft assembly. At 1510 the boost motor was finally recovered and hoisted to the surface where SINO representatives inspected it before it was stowed in the barge. The removal of this boost motor had taken 22 hours diving time and almost had us believing it was welded to the deck of the magazine.

On 16 October the barge was towed into the Gulf of Oman and sunk in 1200 metres of water with it’s dangerous cargo onboard.

The loaded barge (left) en route to the dumping ground, escorted by HMS BOXER.

The whole operation took some 7 weeks and a lot of information was gained on how to tackle this sort of problem if it ever arises again. Hopefully this information will reflect in future training and procurement of equipment.”

Colin Kidman was subsequently awarded the Queen’s Gallantry Medal; Ralph Johnson and James Lynch were awarded the Queens Commendation for Bravery.

Extract from Honours and Awards 1989

Warrant Officer (Diver) Colin “Scouse” Kidman QGM FCDT 26 September 1989

Warrant Officer (Diver) Kidman planned and executed the removal and destruction of a complete outfit of Seadart missiles from the magazine in HMS SOUTHAMPTON, many of which had been severely damaged following a major collision in the Gulf area on 3rd September 1988.

The impact of the collision had badly distorted and buckled the missile handling arrangements and equipment inside the magazine causing a chaotic jumble of missiles, parts of missiles and their associated movement trolleys and rails. The missiles were in highly unsafe positions; one being split in half, one with its warhead buried in the deckhead and the remainder damaged, distorted and displaced to various degrees. In addition the whole magazine was under water.

Mr. Kidman provided a plan of action enabling each missile to be lifted and moved over the ship's side for deposit into a barge. The plan took three weeks to achieve and during the whole of this period he maintained a calm dignity and composure. The highly dangerous and precarious phase of the removal of the missiles, some of which had to be dismantled underwater before they could be freed from their positions, took a further two weeks. Mr. Kidman then supervised the towing of the barge containing the missiles to a deep water disposal ground.

Despite the frightening enormity of the task and risk involved, Mr. Kidman generated enormous confidence in all those who worked for him or had involvement in the proceedings. In tackling the explosive demolitions phase, his selflessness and calculating skill and actions were an inspiration to all, in the knowledge that one small error of judgement or execution could have had catastrophic results. The success of the operation and the safety of the ship and its personnel can be directly attributed to the gallant actions of this humble and dedicated man who demonstrated bravery and leadership of the highest order.

Leading Seaman (Diver) Ralph Johnson FCDT 26 September 1989

QCB awarded for exceptional courage and skill in assisting in the removal of Seadart missiles from HMS Southampton after a major collision in the Gulf area on 3rd September 1988.

Leading Seaman (Diver) James (Jim) Lynch FCDT

QCB awarded for exceptional courage and skill in assisting in the removal of Seadart missiles from HMS Southampton after a major collision in the Gulf area on 3rd September 1988.

Colin “Scouse” Kidman

Colin Kidman was born in Liverpool on 12th September 1947, growing up at Port Sunlight in the Wirral, Cheshire. This was a village built by Lord Leverhulme for his workers employed at the Lever Brothers Factory, later to become Unilever.

He joined the Royal Navy in 1963 at HMS GANGES where he qualified as a Radar Operator. After training he joined HMS LINCOLN stationed in Singapore and was involved in the Indonesia - Malaysia confrontation.

On return to the UK in 1965 he qualified as a Ships’ Diver then as a Clearance Diver in 1967. He took part in experimental dives at the Deep Diving Trials Unit, Alverstoke, then the Far East Fleet Diving Team in Singapore, the Diving School, HMS. VERNON then to HMS GAVINTON in the Middle East, including her return passage to UK on closure of the base in Bahrain.

Colin qualified as a Clearance Diver 1st Class in 1972 and, as a Petty Officer (Diver), served in the Diving School, HMS DRAKE; the Plymouth Clearance Diving Team; HMS BOSSINGTON as Coxswain; the RN Saturation Diving Team in MV SEAFORTH CLANSMAN, including trials with the United States Navy in Panama City. After being rated Chief Petty Officer (Diver) in 1978 he qualified as a USN Master Diver. He subsequently served on exchange at the USN Experimental Diving Unit in Panama City from 1979 until 1981 when he returned to UK and joined HMS CHALLENGER, to run the RN’s Saturation Diving System.

He was the last Fleet Chief Petty Officer (Diver) to be promoted before the Warrant Officer rank was introduced. As a Warrant Officer (Diver) he was on the staff of the Captain, Mine Countermeasures; the Warrant Officer of the Fleet Diving Team; Inspector of Clearance Divers and Special Forces; Warrant Officer of the Portsmouth Clearance Diving Unit. He ended his career at the Diving School in Portsmouth, leaving in 1995.

After retiring from the RN he continued his chosen career as a Diving & Explosives Consultant conducting threat analysis of the hazards of explosive ordnance in different regions of the world for a number of international companies before becoming the Director of Operations for Fellows International Limited, an independent British company. During his time at Fellows he supervised the search and clearance of ordnance, on Land and Underwater on many World-wide and UK sites including The London Eye, The Millennium Bridge and the London Olympic Park. One of his most interesting tasks was in clearing historical ordnance from the vaults from under the historic Vulcan Building in Gunwharf Quays,. He finally retired from a job that he really enjoyed in 2017, at the age of 70.

Colin married Margaret, a local Portsmouth girl, in 1968 and had one daughter Julie. They now have three grandchildren and two great grandchildren all of whom live in the Portsmouth area. Having worked away from home most of his career he now delights in spending most of his time with his family, particularly his great grandchildren, at his home in Drayton, Portsmouth. He has been a key member of the Project Vernon team and enjoys meeting up with his old clearance diving colleagues during the meetings of the RN First Class Divers Association of which he is also the Treasurer.

OPERATION BLACKLEG

16th September 1982 – 28th January 1983

HMS COVENTRY

The recovery of HMS COVENTRY’S secrets from the South Atlantic.

by

Commander Mike Kooner MBE

and

Warrant Officer (Diver) John Dadd BEM

The Requirement

The course of the Falklands War is well documented. However, once hostilities ceased on 14 June 1982 the clearing-up operation commenced. Obviously, the removal of the refuse of war in Port Stanley and other parts of the islands caught the public eye, but elsewhere, offshore, a clearing-up operation of a unique and different kind was necessary. The loss of four modern warships carrying a full range of communications equipment, confidential publications, armament and weapon guidance systems, all of which could be of value to a potential enemy, posed the Ministry of Defence with a huge problem. The answer to the problem was obvious, in theory at least, to recover or destroy anything of intelligence value that remained within the wreck.

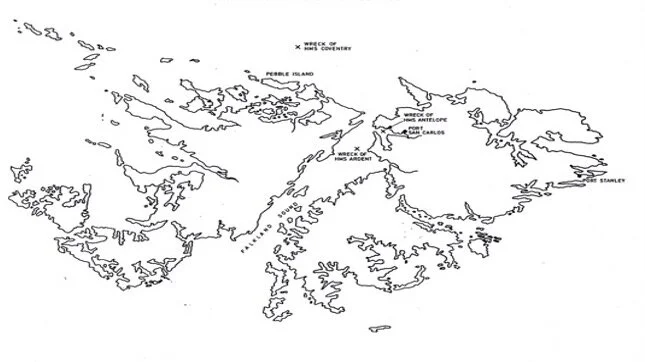

Of the four warships sunk, HMS SHEFFIELD was in water that deep enough for her to be considered safe from interference; HMS ARDENT and HMS ANTELOPE were in the protected waters of the Falkland Sound and San Carlos Water. However, HMS COVENTRY was in an exposed position lying at a depth of approximately 90 metres some 9 miles north of Pebble Island, West Falklands.

The Falkland Islands showing the position of HMS COVENTRY

She was considered to be a potential target for interested parties, employing divers or remotely operated vehicles (ROV) used by technically advanced navies. It was, therefore, imperative to clear HMS Coventry as soon as possible.

Editor’s Note: Royal Navy Clearance Diving operations are, by their very nature, demanding and challenging for the personnel involved and hazardous. Even by those standards the operation described here was exceptional. This was true of the work of most of those involved but is reported only modestly and largely went unrecognised after the event.

It had already been decided in late May that, when hostilities ceased, certain items would need to be recovered. This would necessitate the mounting of a difficult underwater salvage operation the like of which had never been carried out by Royal Navy divers before. It would therefore entail a great deal of forward planning before such an operation could become a viable proposition.

Two main limitations were envisaged which could hamper work on HMS COVENTRY: weather and time. Due to the harsh climate in the South Atlantic any diving operations in those exposed waters would have to be carried out in the relatively benign but short weather window of October to January. This in turn meant that any operation would have to be planned and prepared to meet a sailing date from the UK of mid-September at the latest.

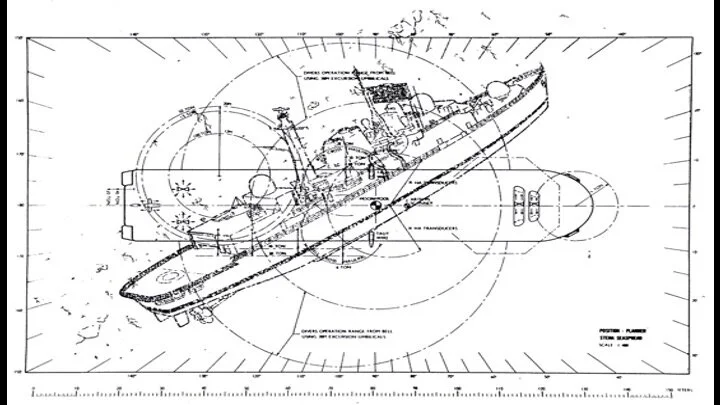

MV STENA SEASPREAD

An ocean-going, deep diving support vessel would need to be identified that was capable of carrying out the salvage. A number of ships were considered but for one reason or another, were rejected as being unsuitable for the task. The decision to charter MV STENA SEASPREAD was taken at the beginning of August.

MV STENA SEASPREAD

There were a number of reasons for choosing MV STENA SEASPREAD:

Availability - she would be available in the time-frame required and her sea-keeping qualities had already had been proven whilst operating in the Falklands as part of the Task Force earlier in the year;.

Endurance - the ship had great endurance, both in fuel and provisions.

Equipment - Stena had a first class and modern saturation diving system which had a good reputation in the North Sea – her normal operating area; was fitted with Dynamic Positioning (DP) whereby she could “hover” over any underwater worksite using thrusters directed by onboard computers; these would be fed information from seabed transponders, radio beacons and taught wire measuring devices.

People - A further consideration was the fact that her crew were now used to working with the Royal Navy and understood the naval organisation. The calibre and professionalism of STENA SEASPREAD personnel was known to be of a high standard and they were aware of the need for tight security in naval operations.

Additional Equipment

Owing to the unique and specialised nature of “Operation Blackleg” a comprehensive range of specialist equipment needed to be fitted prior to her departure south. This included underwater cameras, cutting gear, underwater and through water communications, underwater lighting, a state-of-the-art ROV and a ‘Globe Probe’ underwater observation chamber.

Logistics

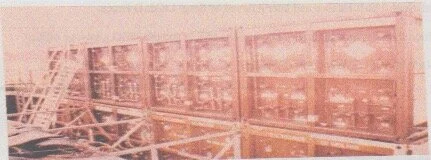

In addition to the usual problems of supplying and supporting a vessel at sea and remote from the UK base, one of the important problems to consider was the logistics of diving gas re-supply.

Gas “Quads”

….and more gas.

Hundreds of thousands of cubic metres of compressed diving gasses would need to be carried. To reduce this requirement as much as possible a Gas Reclaim System (gas miser) was fitted. This could recover gasses from the compression chambers and the exhaled gasses from the divers’ helmets, for purifying and re-using. To ensure sufficient industrial oxygen was available for the cutting equipment, an oxygen generator was fitted to produce oxygen of 90% purity. The fitting of the ‘gas miser’ system and the oxygen generator prevented a logistical nightmare and was one of the technical successes of the operation.

Personnel

The manpower, Naval Party 2200 (NP2200) and STENA SEASPREAD, was commanded by Lieutenant Commander M D Kooner (later Commander).

The rest of the command team was:

XO Lieutenent C Edwards Canadian Armed Forces (later Lieutenant Commander)

WO (Diver) J Dadd.

Logistics: Lieutenant N Hawkins (later Commander)

Medical: Surgeon Commander R Hanson. later relieved by Surgeon Lieutenant Commander D Bruce.

In addition, the RFA provided a communications officer and the MOD a salvage officer.

NP22200 on forming up……

…….and on operations.

The Diving Team comprised 25 divers of various ranks and rates and 13 support personnel, who specialised in diving medicine, supply, technical and communications and ROV operations. A diving supervisor and life support technician employed by STENA UK were initially retained to familiarise the NP with the complexities of the Saturation Diving System.

Saturation Diving

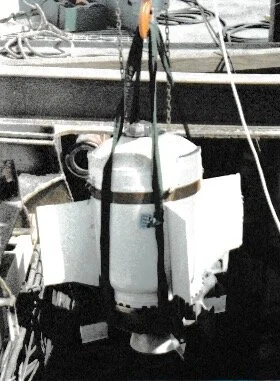

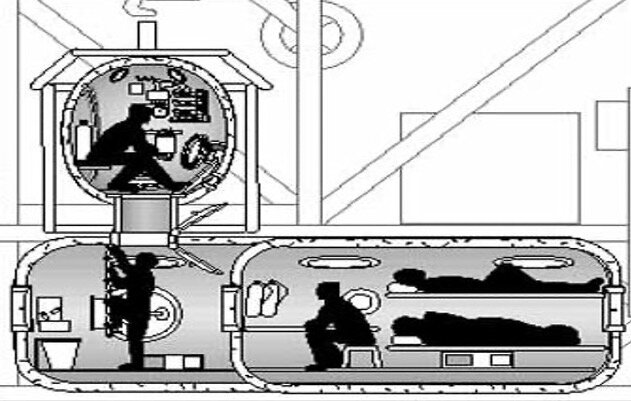

Saturation Diving is employed when there is a requirement for divers to work at depth for long periods. The saturation system onboard MV STENA SEASPREAD consisted of two large onboard compression chambers, each able to accommodate six divers.

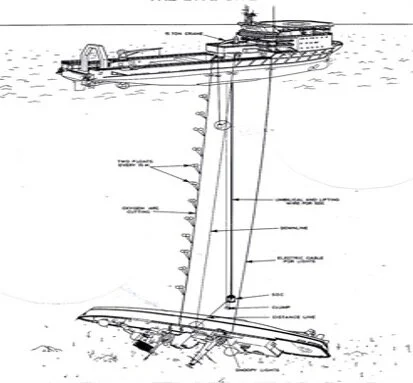

Sat System Layout

Compression Chamber

These are linked by an airlock tunnel on top of which is locked a Submersible Decompression Chamber (SDC) or, as is more commonly known, the Diving Bell.

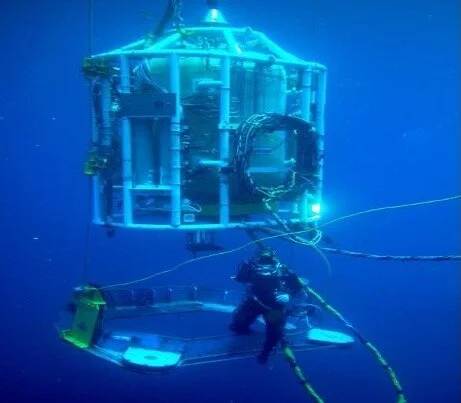

Submersible Decompression Chamber - “The Bell”

The chambers contain bunks and are fitted with small hand operated airlocks for passing through food and essential items; the air lock tunnel also contains a shower and toilet facilities. All the diving equipment is kept in the airlock or bell.

Once the complex has been made ready, divers enter the chambers and, after checks using laid down Operating Procedures (OPs), the whole facility is slowly pressurised with oxy/helium gas, until the pressure inside is equivalent to the average depth (storage depth) of the dive to be undertaken. The divers are left for 24 hours to soak up the inert gas (helium) until their bodies are ‘saturated’. It now doesn’t matter whether the diver stays under pressure for three hours, three days or three weeks, the necessary time to return slowly to the surface (decompression) is the same. The maximum time of a saturation dive is 28 days. However at the depths encountered decompression took approximately three days.

When it is time to go to work, two divers and a bellman climb up into the bell, two heavy metal doors are closed and the space between is vented to atmosphere. The bell can now be unlocked under pressure from the complex and transported in its cradle to the moon pool, which is an aperture cut through the bottom of the ship. Hanging through the moon pool and down to the worksite is a 3 ton clump weight; the bell is attached to the wires of this weight in preparation to guide the bell and divers to the underwater working area.

Passage to the South Atlantic

With all stores and equipment embarked STENA sailed from Portsmouth to return to the South Atlantic on 16 September 1982. A course was set for Falmouth Bay where a short shake-down dive of the saturation system and using and proving the specialist underwater tools packages took place.

On completion of the work-up dive the ship sailed south to the Falkland Islands via Ascension Island.

Of the 25 divers on board only 11 were saturation diving qualified, it was therefore necessary during the 3 week passage south for the 14 non saturation trained divers to undertake a three week saturation qualifying course with medical, theory and practical phases. All passed and gained both Royal Navy and Health and Safety Executive certification.

After a brief stay at the Ascension Island, for more stores, a swim and a test deployment of the observation chamber, it was on to the Falkland Islands arriving, eventually, in the area of operations north of Pebble Island on 12 October 1982.

The Diving Operation

The dive site had previously been marked with seabed transponders laid by Royal Navy Mine Hunters. Having interrogated and picked up signals from these pods the ship was put into DP over the wreck. The clump weight was lowered through the moon pool with a Cyclops ‘Pan and Tilt’ low-light camera attached and 20 minutes later HMS COVENTRY was sighted for the first time.

Diagram showing HMS COVENTRY’s position and angle on the seabed.

By using the camera for navigation, a complete survey was carried out producing five hours of video showing the whole wreck; she was found to be lying on her port side. Co-ordinates had been fed into the onboard computers which would allow the moon pool to be manoeuvred in three metre increments over any part of the ship that would eventually need to be worked on. Before sailing, a priority list of items to be dealt with had been drawn up. This allowed the CO to plan dives that were designed to recover high priority equipment first, whilst taking into account the location of various compartments and the relative difficulty of entering them. Thus, by the evening of 13 October 1982, when the divers were pressed down, the NP and ship were worked up and prepared to carry out the first major saturation dive on the wreck of HMS COVENTRY.

The Dive Site

The first two diving excursions were notable for mixed reasons. On the first, the dive leader recovered HMS COVENTRY’S battle ensign, hauling it down on its halyards. A signal was sent “Have today lowered HMS COVENTRY’S battle ensign, her halyards, my divers.” The ensign was washed, pressed and sent to UK for the Commander-in-Chief Fleet. Quite an emotional time!

The success of this first excursion was tempered by events which affected the next diver out of the bell, who was employed venting gasses from the hull. The weather had deteriorated and the diver was clearing up the dive site ready to return to the bell, when a complete computer failure occurred causing a “DP run-off”. The ship was now completely at the mercy of the wind and tide. Fortunately, showing much grit and determination, the diver fortunately managed to swim back to the bell with the help of the bellman, hauling him in on his umbilical and was safely recovered, shaken but not injured. However, had he been inside the wreck his umbilical may well have been severed and it is unlikely he could have returned to a diving bell which was disappearing at a rate of knots. At this stage the working down-line parted, striking the bell and fouling one of the DP thrusters. Not a good start and a loss of faith in Dynamic Positioning by the divers.

Editor’s Note: The diver involved was Leading Seaman Diver Martin Jenrick (later Lieutenant Commander). Although badly shaken by this experience he continued with the operation and later carried out at least one further saturation dive on the wreck.

It was during these first excursions that it was realised there was a serious communications problem between diver and Dive Control. Although the divers could hear the Dive Supervisor quite well, the helium effect on the divers’ (Donald Duck) voices and the background noise from the ships DP thrusters caused the controllers, quite literally, a severe headache. However, after half a dozen ‘say again’ requests, the message would eventually get through.

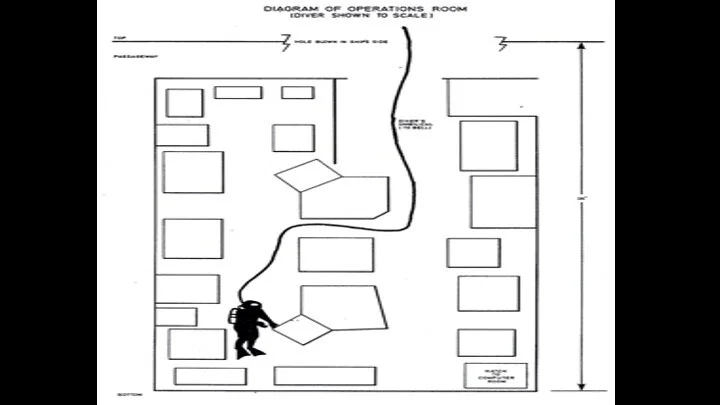

The plan of entry into the wreck was to cut an access hole in the hull directly above the target compartment. This was achieved by the diver marking the area with waterproof crayon, as directed in the pre-lockout brief and Dive Control working from scale drawings of the ship, his position was then monitored by the underwater camera and pictures sent via the ROV. This area was vented by punching holes into the patch with a Cox’s Bolt Gun and then cutting around the perimeter with oxy/arc cutting gear; this was then stripped from the ship with a 15 ton crane.

Having removed the patch the diver faced a variety of pipes and fibre glass insulation lagging, lining the passageways; this broke up and entered their hot water suits which made for a very itchy few hours. The pipes would be dealt with very carefully as they contained anything from diesel oil to dirty waste water. Although this method of entry into the ship proved successful it had its problems. Many blow backs from the cutting gear were experienced (“blow-backs” are common), but the severity is unpredictable due to the build-up of various explosive gasses, plus diesel and oxygen, nucleating to give a nasty boost. Indeed, throughout the operation two divers had the face plates on their helmets blown out resulting in flooded masks and perforated eardrums. One was so severely injured, as to need casualty evacuation to the UK.

Editor’s Note: Leading Seaman Diver (Ginge) David suffered perforated ear drums and Leading Seaman Diver Steve Clegg had a cracked faceplate.

Once into the bowels of the ship the divers faced complete chaos. Entering a ship lying on its side is disorientating enough but, to be faced in darkness with bomb damage, sharp, twisted and shattered metal and yard after yard of electric cable, from which was hanging heavy computer consoles, presented a severe and hazardous problem to the divers. On a number of occasions divers became entangled. . It was, however, up to the diver to free himself, as dive policy dictated that, to minimise the risk, only one diver would enter the wreck at a time, with his buddy tending his umbilical at the point of entry.

Editor’s Note: Ex-divers involved in the operation considered that the role of the Diver (2 outside the hull) was to enter the hull to rescue the Diver 1 if necessary

PO Diver Harrison (later CPO) found himself entangled, disorientated and trapped: the team could do nothing to extricate him. His training, determination, and bravery coupled to his calmness under extreme duress enabled him to, somehow, extricate himself. He was later awarded the Queen’s Gallantry Medal.

Editor’s Note: It was subsequently reported that Petty Officer Diver Harrison (Diver 1) became entangled at least twice. On one occasion he was assisted, indeed rescued, by Diver 2, Leading Seaman Diver Ray Suckling. In another event the second diver, Leading Seaman Diver Graham Wilson (later Lieutenant Commander) was asked to assist but, on entering the wreck, he found that Harrison had managed to free himself.

Diagram of the Operations Room - Diver shown to scale

The first priorities were to enter various security compartments and remove specific classified aerials. A simple entry in the dive log summed up the team’s feelings, “Diver in EWO, Yahoo!” (EWO is the Electronic Warfare Office which contains highly classified detection equipment).

It was now a case of working through each specified compartment, as per the priority list. This included opening safes and removing confidential items, mainly books and tapes. Prior to deploying, the combinations of all the safes had been given to the CO. It soon became apparent, however, that opening a safe with the combination lock underwater was a non-starter. It was quickly found though, that the ‘Clucus’ cutting equipment could open a heavy military safe in 15 seconds!

The Captain’s cabin and safe were cleared and en-route to the bell. HMS COVENTRY’s prized “Cross of Nails” was recovered along with the other items. The diver was spooked by the Cross as he claimed it simply floated into his hands. Entry was gained into other target areas that were cleared quickly. This rapid progress was a reflection of the confidence and efficiency that the team had now built up and were bringing to the job. Further progress was made when entry was gained into the Type 909 radar and Ship’s Offices which were cleared of all classified material.

Once all internal tasks were completed the team were then able to concentrate on the outside tasks of clearing ordnance and specific aerials. Where possible, aerials were cut and removed and it was at this stage that experts were proven incorrect. Prior to deployment the Officers, Warrant Officer and Senior Rate Divers were informed that an explosion in excess of 70 metres could not be initiated from the surface using current in-service equipment. As a test, a 4lb PE pack was placed on the Sea Dart missile still on its launcher, with an initiating tail of Cortex to the surface. When the divers were recovered and STENA SEASPREAD had moved off station to a safe distance, the demolition charge was initiated and the missile was destroyed.

Having proved the feasibility of deep demolitions it now became a most useful tool in dealing with items around the outside of the ship.

By late December the team had completed four back-to-back saturation dives with the system being ‘pressed down’ for virtually three months and the divers spending close on 600 hours diving in or around the wreck. The product of this highly efficient team-work meant that the operation was concluded earlier than planned. All MOD and the Commander in Chief Fleet’s original instructions had been carried out and all that remained to be done was survey the wreck and clear the seabed of transponders.

The system was pressed down for the last time to carry out these remaining jobs. As a final, poignant act of remembrance a White Ensign was lowered to the divers who hoisted it on the wreck.

Passage to the UK

Having said our goodbyes, MV STENA SEASPREAD sailed from Port Stanley on 30 December 1982 with six divers still undergoing decompression. Finally, all could relax a little and stand down from working a 24 hour day on a 12 hours on/12 hours off watch-keeping routine. The continuous pace and sheer hard work of the operation had started to take its toll both physically and mentally on the whole team, some of whom had been in the South Atlantic during the war and its aftermath for most of 1982.

On the passage north all were occupied cleaning and painting the areas of the ship that were used for the operation and were the NP responsibility and packing equipment ready for disembarkation.

STENA SEASPREAD arrived back in Portsmouth 28 January 1983 to be met by the Flag Officer Portsmouth, our families and friends.

Conclusion

In conclusion, when NP2200 deployed from Portsmouth they were embarking on a voyage into the unknown. The CO was briefed to expect casualties due the perceived nature of the unfamiliar task in a hostile environment.

This is an account of the epic task that took place after the turmoil of the Falklands conflict. Good planning was the cornerstone on which this operation was built. Backed by a superbly professional and dedicated support team. It was the divers on-site, however, who, through their stamina, courage and skill, enabled Naval Party 2200 to achieve the task objective.

The Commander in Chief Fleet sent a signal commenting on the outstanding professionalism of the Naval Party and continued “It has been a unique saturation diving and salvage task and in many respects the most difficult task ever executed by any naval or commercial diving team”

HMS COVENTRY may tragically have been sunk in action but her secrets would remain forever secret. That was what Operation BLACKLEG was all about.

HONOURS & AWARDS FOR OPERATION BLACKLEG

PO(D) Michael (Harry) Harrison NP2200

Awarded the QGM

During the period 10th to 30th November 1982 a Royal Navy Saturation Deep Diving Team was engaged in salvage operations off the Falkland Islands, in which Petty Officer (Diver) Harrison was instructed to recover items from one of Her Majesty's Ships [HMS Coventry], which had been severely battle damaged. Though working in extremely unpleasant, hazardous and dark conditions, and despite becoming entangled on two separate occasions with hanging debris, Harrison persevered with the task, putting himself at grave personal risk. Throughout the operation he showed the very finest example of skill and courage to his colleagues which inspired a notable success in what was possibly the most dangerous task ever undertaken by a Royal Navy Diving Team. His outstanding professionalism, bravery and total disregard for his own safety were in the highest traditions of the Service.

Lieutenant Commander Michael David Kooner Royal Navy

Appointed MBE

For service as the Commanding Officer MV STENA SEASPREAD and NP2200 during Operation BLACKLEG

CPO(D) Barry (Blondie) Limbrick NP2200

Awarded the BEM

For his involvement in the salvage of equipment from HMS COVENTRY in the South Atlantic.

Read a first-hand account by one of the COVENTRY Divers.

Watch a film about the sinking of HMS COVENTRY

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of Operation BLACKLEG….

…a painting by Dave CoburN

“FRACTION OF a SECOND”

“In a fraction of a second they are projected into eternity” ~ unknown.

On the 40 th anniversary of Operation Blackleg undertaken by the Royal Navy’s Clearance Diving Branch. This historic dive carried out by the Deep trials and Saturation Diving Team (NP2200) successfully recovered or destroyed at a depth of 300ft all NATO sensitive equipment and documents from the war grave HMS Coventry.

On May 25th 1982 the type 42 class destroyer was sunk of West Falkland Island by Argentine jet fighters dropping three 1000lb bombs deep into the ship, of which only two detonated.

The painting is entitled “ Fraction of a Second” commissioned by Leading Diver Ray Sinclair (formerly Suckling) The oil on canvas art work depicts his final dive on HMS Coventry. It shows him strapping a 4lb plastic explosive pack to the armed warhead.

Commissioned to honour all the divers of NP2200, who in the most harrowing and dangerous conditions performed as a team to successfully complete the arduous mission. The painting also honours all military personnel who risk their lives in bomb and mine disposal operations.

Forever on watch ~

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning We will remember them.” ~ Robert Laurence Binyon

Find out more about modern Minesweepers, Mine Hunters, Diving Teams and ongoing operations here.

A SHORT HISTORY OF DIVING

By Rob Hoole

According to Sir Robert Davis’ book, Deep Diving & Submarine Operations, archaeological excavations have revealed mother-of-pearl inlays dated as early as 4500 BC which must have been gathered by breath-held divers. Although this is the earliest indication of man’s first technique for underwater work, there are many other examples of early attempts at diving, both military and commercial. For many years, an Assyrian frieze (900 BC) in the British Museum was thought to depict an underwater warrior breathing air from a goatskin lashed underneath himself. However, closer inspection reveals this to have been a flotation device kept inflated via a breathing tube by the user – the world’s first example of water wings!

Several authors refer to abortive attempts at diving throughout the earlier part of the first millennium but it was not until Becker (1715) that a working personal diving apparatus was demonstrated in London with a diver reportedly staying under water for about an hour. In 1754, Dr Richard Pococke’s Travels in England contains an account of divers engaged in salvage operations on a man of war off the Needles who were supplied with air from the surface and worked underwater for 5 minutes at a time. In 1783, the Encyclopedie Methodique refers to similar operations on the wreck of the HMS Royal George at Spithead.

Later designers of theoretical (and largely problematical) diving apparatus included Freminet (1772), Forfait (1783), Pilatre de Rozier (c.1783), Klingert (1797), Burlet & Sardou (1798), Forder (1802), Fullerton (1805), Drieberg (1808) and James (1825) who designed the first self-contained diving dress provided with a supply of compressed air although it does not seem to have ever been developed or tested.

In 1819, Augustus Siebe introduced the first pattern of his diving dress and helmet. The original form was known as the ‘open’ dress and consisted of a brass ‘hard hat’ helmet, equipped with a viewing port, attached to a jacket reaching to the waist. The helmet was supplied with air under pressure from a pump on the surface and could escape freely at the diver’s waist. In 1837, Siebe modified his original ‘open’ dress by enclosing the diver (apart from his hands) in a waterproof rubberised canvas suit to which the helmet was attached. This was known as Siebe’s ‘closed’ dress and was to become the world’s Standard Diving Dress, the most widely used diving equipment until World War II. In a modified form, it can still be found in use throughout the world.

In 1866, the first self-contained open-circuit (breathed air exhausted) breathing apparatus was designed by Frenchmen Benoist Rouquayrol and Auguste Denayrouze. This was a demand regulator system mentioned by Jules Verne in his classic ‘Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea’. This book, written in 1869, described the apparatus and its use in a conversation between Captain Nemo and Professor Arronax.

In 1878, the first practicable self-contained closed-circuit (breathed air recycled) breathing apparatus was designed by Henry A Fleuss, an English merchant seaman, in association with Siebe, Gorman & Company. This consisted of a watertight face mask connected by a tube to a breathing bag, a copper cylinder of air compressed to 39 atmospheres and a chamber of CO2 absorbent (rope yarn soaked in caustic potash) through which the air was breathed. Fleuss’s diving set was used successfully during work in flooded collieries in 1880 and by Alexander Lambert in his famous exploit in saving the flooded Severn Tunnel in 1882. In collaboration with Fleuss, R H (later Sir Robert) Davis modified this equipment to produce the Siebe Gorman ‘Proto’ and ‘Salvus’ breathing sets used by British, American and other Allied armies for mining, tunnelling and other military operations during the First World War. Subsequently, these designs led to the Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus (DSEA) that was intended not only for submarine escape but also for work on the sea bottom and about ships’ hulls.

In 1943, the development of a self-contained open-circuit breathing apparatus was revisited by a French naval officer, Commander LePrieur. His design used a tank of compressed air but did not include a demand regulator. The diver was thus forced to spend much of his time manipulating a valve to control his air supply. This, coupled with a short endurance, severely limited the practical use of the equipment. In 1943, two other Frenchmen, Captain Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Mr Emile Gagnan successfully demonstrated a set with an improved demand regulator and high pressure air tanks and this became the first truly successful open-circuit self-contained diving apparatus. Thus, the ‘aqualung’ was born as used by the Royal Navy and thousands of SCUBA (Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus) divers to this day.

THE HISTORY OF MILITARY AND NAVAL DIVING

by Rob Hoole

MILITARY DIVING

The first recorded military diving occurred in 1838 when a Royal Engineer, Colonel Pasley, later Maj Gen Sir Charles William Pasley FRS KCB (1780 - 1860), of the School of Military Engineering at Chatham, undertook to demolish the wreck of a collier blocking the Thames fairway at Tilbury. After unsuccessful attempts to place explosive charges using the diving bell from the Naval Dockyard, Pasley trained a number of his soldiers in the use of various diving equipment. Having first tested the concept himself, he became the first Service diver on 28 April of that year. Within a short period, charges had been successfully laid by divers of the Royal Sappers and Miners and the wreck was demolished. Between 1839 and 1844, Army divers under the command of Colonel Pasley conducted salvage operations and then disposed of the wreck of HMS Royal George which was posing a menace to navigation at Spithead. During this period, Colonel Pasley evaluated a number of different types of diving equipment and, in his final technical report, recommended the use of August Siebe's enclosed 'standard' diving dress for ‘public service’.

HMS EXCELLENT’s CONNECTION

Having persuaded the Royal Navy of the advantages of Siebe’s diving equipment over the unwieldy dockyard diving bell, Colonel Pasley detached Lance Corporal Jones, Royal Engineers to HMS Excellent in 1844 to train a party of 13 petty officers and seamen in its use. A Royal Navy diving school was established at Whale Island and RN diving became the responsibility of the Gunnery Branch at HMS Excellent while Army diving continued to be the responsibility of the Royal Engineers.

NAVAL DIVING AND EXPLOSIVE ORDNANCE DISPOSAL (BOMB & MINE DISPOSAL)

HMS Vernon, the name eventually given to the shore establishment, was originally that of a hulk anchored in Fountain Lake. Initially a tender to HMS Excellent, it was used for Torpedo and Mining training from 1872 but became an independent command on 26 April 1876 when it moved to Portchester Creek to become the home of the Torpedo Branch.

During the First World War, work was concentrated on torpedo trials and training and the research and development of anti-submarine devices and training in their use as well as mines and all matters electrical. On 1 October 1923, HMS Vernon (or ‘The Vernon’ as it came to be known) was established ashore on the site of the old Gunwharf (now the millennium development known as Gunwharf Quays) where Mining, Whitehead [torpedo] and Electrical departments were formed.

During the Second World War, HMS Vernon became responsible for mine disposal and mine countermeasures. Her officers and scientific staff achieved several coups involving the capture of mines and the development of countermeasures. One of the earliest of these was the rendering safe and recovery of the first German magnetic mine (Type GA) at Shoeburyness on 23 November 1939. For this deed, Cdr John Ouvry was decorated with the DSO by King George VI at a ceremony on HMS Vernon’s parade ground on 19 December 1939. Others decorated at the same time for this, and other tasks where mines were rendered safe for recovery and examination, were Lt Cdr Roger Lewis (DSO), Lt J E M Glenny (DSC), CPO C E Baldwin (DSM) and AB A L Vearncombe (DSM). Of particular note, these were the first Royal Naval decorations of the war.

In June 1940, the first attempt to render safe a ground mine by divers was made in Poole Harbour, Dorset. A diving unit from HMS Excellent, supported by divers trained in Rendering Mines Safe (RMS) techniques from HMS Vernon, successfully removed the fuze from a Type GC mine underwater although the mine exploded as it was towed inshore. For his central role in this task, Able Seaman Diver R G Tawn was subsequently awarded the DSM. On discovering the skill of HMS Vernon’s mine technicians, the Germans placed booby traps in some mines. One was fitted with a small explosive charge that detonated when the mine was stripped in the mining shed at HMS Vernon on 6 August 1940 causing the deaths of 1 officer and 4 ratings and serious injuries to other personnel. Following this, mines were stripped and examined at a nearby disused quarry that was nick-named HMS Mirtle (short for Mine Investigation Range).

Various sections of HMS Vernon were dispersed to sites throughout the country following heavy air raids, one of which demolished Dido Building and killed 100 people in a single night. On 3 May 1941, the main part of HMS Vernon was evacuated to Roedean Girls’ School at Brighton (Vernon (R)) where bell pushes on the dormitory bulkhead were purportedly labelled ‘Ring for Mistress”. Other sites included Havant, Purbrook, West Leigh, Stokes Bay, Hove, Dartmouth/Brixham, Helensburgh, Edinburgh and Port Edgar.

Although many naval divers were trained at HMS Vernon in Rendering Mines Safe (RMS) procedures as members of the Mine Recovery Section during the Second World War, it was not until 1 October 1944 that responsibility for naval diving passed from the Gunnery Branch, still based at HMS Excellent, to the Torpedo Branch based at HMS Vernon. This brought Minewarfare (both mining and mine countermeasures) and Diving under the same organisation (the Director of Torpedoes and Mining) for the first time. Owing to the wartime evacuation measures, a new diving school and experimental station known as Vernon(D) was set up at Brixham on 27 Oct 1944. The RN Superintendent of Diving, responsible since 1942 for the Admiralty Experimental Diving Unit (AEDU) based at Siebe Gorman and Co, Tolworth, Surrey and for the coordination of diving training in addition to research and development, moved to Brixham together with HMS Tedworth, the RN Deep Diving Tender. Almost immediately, Vernon(D) became overwhelmingly occupied with the training and support of ‘P’ (Port Clearance) Parties (Naval Parties 1571-1575 and 3006) until 1 October 1945 when the organisation moved back to HMS Vernon proper at Portsmouth.

On 10 October 1946, the Torpedo Branch divested its Electrical responsibilities to the recently formed Electrical Branch and merged with the Anti-Submarine Branch to form the Torpedo and Anti-Submarine (TAS) Branch. Hence, the TAS Branch assumed responsibility for naval diving. HMS Vernon remained the home of the TAS Branch until the Summer of 1974 when it was devolved to HMS Dryad prior to the formation of the Operations Branch in early 1975. Training in Diving, Demolitions and Minewarfare, along with Naval Control of Shipping and, for a time, Seamanship, continued on the site of HMS Vernon even after it ceased to be an independent command on 31 March 1986 and was renamed HMS Nelson (Vernon Site). In 1987, the establishment was renamed HMS Nelson (Gunwharf) and briefly became Headquarters for the Commandant General Royal Marines before his move to permanent accommodation on Whale Island. In November 1995, Minewarfare training was shifted to the School of Maritime Operations (SMOPS) HMS Dryad. Diving training, together with the Superintendent of Diving, the Fleet Diving Headquarters, the Fleet Clearance Diving Team and the Portsmouth Area Clearance Diving Team moved into new accommodation on Horsea Island and the old Vernon establishment closed its gates for the last time on 1 April 1996.

FULL CIRCLE

Following a long period when Royal Naval diving training was based on the same site at HMS Vernon and its successors (together with Army diving training from 1985), it has been conducted at the Defence Diving School on Horsea Island (together with that of the Army) since September 1995, back under the auspices of HMS Excellent where it all started. Thus, naval diving training has come full circle. The Army’s diving training tank at Horsea is even named after Colonel Pasley to commemorate the important role he played in instigating military diving.

DIVERS IN THE ROYAL NAVY

Until roughly 2000, there were two types of diver in the RN: the Ship’s Diver (formerly the Shallow Water Diver), who could be of any rank or specialisation and was trained to use self-contained open-circuit compressed air diving apparatus to search the ship’s bottom for explosive devices or perform simple underwater engineering tasks; and the Clearance Diver (CD) who is a specialist trained in the use of all types of service diving equipment including surface demand and closed-circuit mixture breathing apparatus to perform deeper diving, Explosive Ordnance Reconnaissance (EOR), Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD), salvage operations and complex underwater engineering tasks. Today, only the Clearance Diver remains.

THE ROYAL NAVY CLEARANCE DIVING BRANCH

by Rob Hoole

Clearance Diving takes its name from the operations carried out towards the end and after the Second World War to clear the ports and harbours of the Mediterranean and Northern Europe of unexploded ordnance and booby traps laid by the Germans. This work was undertaken by RN Rendering Mines Safe (RMS) and Bomb Disposal Units and later by Port Clearance Parties or ‘P’ Parties, two of which (Naval Parties 1571 and 1572) went into action soon after D-Day to clear the vast quantities of unexploded ordnance and general debris left after the Allied invasion. They were joined later by other ‘P’ Parties including 'P' Parties 1573, 1574, 1575 and 2444 (many of which had Commonwealth naval personnel) and 'P' Party 3006 manned by the Dutch. The 'P' Parties were formed under the Admiralty's Director of Minesweeping because they were, in effect, a form of minesweeping. On 1 October 1944, all Royal Navy diving, including the 'P' Parties, was transferred to the Director of Torpedoes and Mining.

Work in the European theatre continued until well after the end of the war. Most of the 'P' Parties were disbanded, together with HMS Vernon(D) at Brixham, on 30 November 1945. The exceptions were 'P' Party 2444, which was still operating at Dunkirk, and 'P' Party 2443 which had been formed in June 1945 to deal with residual suspected unexploded ordnance around the UK coast after the war and became based at HMS Vernon, Portsmouth.

Members of RN RMS and Bomb Disposal Units and the later ‘P’ Parties were among the most highly decorated of the war. While the RMS and Bomb Disposal Units suffered many grievous casualties, not a single member of a ‘P’ Party was lost in action although AB William Brunskill died of wounds after a German V-2 rocket hit the Cinema Rex in Antwerp where he was watching a film on 16 Dec1944. All this was despite having cleared the ports of Cherbourg, Caen, Dieppe, Le Havre, Boulogne, Rouen, Calais, Antwerp, Ostend, Terneuzen, Zeebrugge, Flushing, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Hamburg, and Bremen. Sixty mines were cleared at Bremen alone. Lt Cdr Lionel ‘Buster’ Crabb was one of those involved in clearance operations in Italy having seen success against the limpet mines placed on ships in Gibraltar harbour by Italian charioteers operating from a ship interned across the bay in Algeceiras harbour. On 19 April 1956, he was to disappear in mysterious circumstances when the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze brought Khrushchev and Bulganin to Portsmouth.

OTHER NAVAL ORGANISATIONS

Other naval organisations that made a contribution to the CD Branch included:

Standard Divers.

These ‘professional divers’ of pre-war days were trained at the Gunnery School at HMS Excellent in Portsmouth. Among other things, they carried out much research and experimental work in conjunction with eminent scientists such as Sir Robert Davis of Siebe Gorman and Professor J S Haldane for the furtherance of diving knowledge. Officers and sailors, mainly from the Gunnery Branch, became Qualified Deep Divers. They served in the Fleet as Clearance Divers for some time after the war but were gradually phased out or transferred to the CD Branch.

Admiralty Experimental Diving Unit.

The AEDU was formed in 1942 under the command of the first RN Superintendent of Diving, a submarine officer from HMS Dolphin, Lt Cdr (later Capt) W O 'Bill' Shelford. The unit was based at the Tolworth, Surrey works of Siebe Gorman and Co Ltd and a close partnership was formed during the war years. Here, all the diving equipment was developed for human torpedoes (chariots), midget submarines (X-craft), mine recovery parties and, later, for the ‘P’ Parties. An exhaustive programme of human experiments was conducted on oxygen diving and other physiological problems associated with diving with Professor J S B Haldane (son of J S Haldane) acting as the adviser. AEDU continued to perform its work at HMS Vernon until shortly before its closure.

The Mining Department and the Mine Design Department of HMS Vernon.

In 1875 HMS Vernon was made responsible for the development and disposal of sea-mines. During the Second World War, the Mining Department was set up under the Director of Torpedoes and Mining at the Admiralty with responsibility for the recovery of enemy mines, both above and below water. Rendering Mines Safe (RMS) teams were responsible for the disposal of unexploded mines. Recovered mines were exploited by the Mine Design Department to discover how they worked and, thereby, how they could be swept or countered. On 1 October 1944, responsibility for naval diving passed from the Gunnery Branch to the Torpedo Branch whereupon the Director of Torpedoes and Mining assumed responsibility not only for diving equipment but for the co-ordination of training as well.

Landing Craft Obstruction Clearance Units.

The ‘LCOCUs’ were a vital part of the D-Day invasion forces in Normandy. Four Royal Navy and six Royal Marines units comprising 120 divers wore newly developed neoprene suits with 'blast proof' kapok jackets underneath, helmets, breathing apparatus and fins. They laid the foundations for the Very Shallow Water (VSW) and beach clearance techniques in use today. Those remaining after the war were eventually incorporated into the Clearance Diving Branch.

Naval Bomb Disposal Teams.

By 1939, concurrently with the formation of Royal Engineer Bomb parties, the Admiralty and Air Ministry had set up their own separate and distinct Bomb Disposal organisations, each with an exclusive responsibility to its parent service. In August 1940, the UK Joint Service Bomb Disposal Charter was raised to outline and establish inter-Service responsibilities for UK Explosive Ordnance Disposal. Naval Bomb Disposal Teams were set up under the Directorate of Naval Ordnance under the Director of the Naval Unexploded Bomb Department (DUBD) to discharge the Royal Navy’s responsibility for dealing with unexploded bombs on its own property. By 20 September 1940 there were Naval bomb disposal teams at 27 shore establishments. Each team was led by a BSO (Bomb Safety Officer) who was normally a Sub Lieutenant RNVR or Commonwealth equivalent of the RNVR.

One of the BSOs was an American called Draper L Kauffman. He graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1933 but retired to civilian life because of weak eyesight. In 1939 he joined the French Ambulance Service and was captured by the Germans when they overran Holland and Belgium. Upon his release as a citizen of a neutral country (USA), he joined the Royal Navy as a Sub Lieutenant RNVR (Royal Naval Voluntary Reserve) and was trained as a BSO. He performed bomb disposal duties for 14 months until October 1941 when, following an accident, he returned on leave to Washington. Here, he was approached by the US Bureau of Ordnance and asked to establish a US Bomb Disposal School. Thus, Lt D L Kauffman RNVR became Lt D L Kauffman USNR and Officer-in-Charge of the first US Bomb Disposal School. He was subsequently awarded the Navy Cross for bomb disposal work at Pearl Harbour and finally retired from the USN as a Rear Admiral after establishing the US Navy's first Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs), the forerunners of the Sea, Air, Land Teams more commonly known as the SEALs.

In September 1944, the duties performed by DUBD were taken over by the Director of Torpedoes and Mining (DTM), the new department thus formed being known as DTM (Bombs and Mine Disposal Section). This new branch, based at HMS Vernon, thus controlled the BSOs (Bomb Safety Officers), the RMS (Rendering Mines Safe) personnel (who were already an integral part of DTM) and the Land Incident Section.

X-Craft and Chariot Crews.

These belonged to the Submarine Branch but the crews were required to train as divers. Much of the work devoted to their training and to the development of their equipment was conducted by AEDU and contributed to the diving techniques and equipment in use today. X-Craft, with divers embarked for cutting through defensive nets and attaching limpet mines, attacked the German battleship Tirpitz in Norway in September 1943 and were also used successfully in the Far East. British charioteers operated in the Mediterranean and the Far East.

THE END OF THE WORLD WAR II

With the end of the war, Vernon(D) at Brixham was closed on 1 Oct 1945 and ‘P’ Party 2443 moved its headquarters to HMS Vernon at Portsmouth but only for a short period. It was decided to integrate the ‘clearance’ divers more closely with the mine countermeasures establishment at HMS Lochinvar in Port Edgar on the Firth of Forth and this is where the members of the last ‘P’ Party on the Continent ('P' Party 2444) were sent in March 1946 after having cleared Dunkirk. In the meantime, HMS Vernon became the centre for Deep Diving and AEDU moved here from Siebe Gorman at Tolworth. Something of a division then sprang up between the deep divers at Vernon (the ‘Steamers’) and the Clearance Divers at Lochinvar (the ‘Corkheads’).

FORMATION OF THE CLEARANCE DIVING SPECIALISATION

In 1950, a Home Station Clearance Diving Team was set up and other Clearance Diving Teams were soon established to support the Mediterranean Fleet and the Far East Fleet. In 1951, clearance diving training moved from Lochinvar to Vernon and a new Clearance Diving School was established combining the training of clearance divers with that of ‘deep’ divers. This school also took on the new task of training Shallow Water Divers (later called Ships’ Divers) so that every ship had a properly equipped air diving capability under its own Diving Officer to conduct ship’s bottom searches and undertake simple underwater engineering tasks.

On 3 December 1948, 'P' Party divers were officially renamed Clearance Divers in accordance with Confidential Admiralty Fleet Order 341/1948. On 7 March 1952, the Clearance Diving (CD) specialisation, under the auspices of the TAS Sub-Branch of the Seaman Branch, was officially introduced under Admiralty Fleet Order (AFO) 857/52 although a training nucleus had been set up some two years earlier to take advantage of the few remaining men with wartime experience. These officers and ratings had, in the main, qualified as Shallow Water Divers trained to use the Sladen ‘Clammy Death’ diving dress and oxygen breathing apparatus. They were joined by other officers and ratings Qualified in Deep Diving (QDD).

On 25 February 1966, the Minewarfare and Clearance Diving (MCD) Sub-Specialisation of the Seaman Branch was formed in accordance with Defence Council Instruction 278/66. Seaman Branch officers already qualified as CD and TAS automatically became MCD Officers while those qualified only as CDOs undertook a conversion course to be trained in Minewarfare, until then, the prerogative of TAS Sub-Branch officers. TAS (UW) and (UC) ratings of the Seaman Branch continued to perform Minewarfare duties until 1975 when the Minewarfare (MW) Sub-Branch of the Operations Branch was formed together with the Diver (D) Sub-Branch. In 1981, the MCD Sub-Branch of the Operations Branch took over responsibility for demolitions training from the Sonar (ex-TAS UC) Sub-Branch.

DEEP DIVING

In June 1948, HMS Reclaim entered service and was to be the RN’s deep diving tender for the next quarter of a century. Almost immediately, she grabbed the world’s headlines when, within two months of commissioning, Petty Officer Wilfred Bollard claimed the world deep diving record at 535 feet. She went on to undertake several more headline grabbing tasks by finding, and often assisting in the deep salvage of various submarines (including HMS Affray in April 1951), aircraft, helicopters and weapons lost during trials. On 12 October 1956, Lt George Wookey RN dived from HMS Reclaim to set a new deep diving record of 600 feet in Sorfjord, Norway. The CD branch retained a deep diving capability using the venerable Deep Diving & Submarine Rescue vessel HMS Reclaim, the chartered diving support vessel MV Seaforth Clansman and the short-lived Seabed Operations Vessel HMS Challenger as saturation diving platforms for NP 1007 until the early 1990s when naval deep diving was abandoned because it became more cost-effective to use commercial resources when required.

OTHER ACHIEVEMENTS

The CD Branch has been kept active throughout its existence. The Mediterranean CD Team undertook the clearance of WWII ordnance in Grand Harbour, Malta. During Operation Rheostat in 1974/5, the Fleet Clearance Diving Team worked with RN MCMVs to clear the Suez Canal of ordnance and other military debris following the Arab-Israeli 6 Day War. The final tally included 209 tons of TNT bombs of various sizes, about 800 ant-tank and anti-personnel mines, 6,000 rounds of ammunition and 70 various missiles. During Operation Hemicarp in 1977, RN CDs co-operated with their US counterparts to clear ex-US and Japanese WW II ordnance from the waters of Tarawa and Tuvalu in the Gilbert and Ellis Islands. On a more peaceful note, 35 RN CDs worked with 18 Egyptian divers in 1977/78 to shift 16,000 tons of mud and 320 blocks of stone during the movement of important Egyptian monuments submerged by the construction of the Aswan Dam to a site replicating Philae on Agilkia island.

CD teams worked in particularly arduous conditions conducting bomb and mine disposal during Operation Corporate in the Falklands in 1982 and in the Red Sea during Operation Harling in 1984. In 1987, they cleared Iranian mines in the Gulf of Oman and in the Persian Gulf during Operation Cimnel. In 1991, they were back in the Persian Gulf during Operation Granby, this time clearing hundreds of Iraqi mines laid off the shore of Kuwait. Most recently, CDs embarked in RN mine hunters were involved in Operation Allied Harvest (the clearance of allied bombs jettisoned in the Adriatic during the Bosnian and Kosovo conflicts) in 2000, and Operation Cleanex (the clearance of wartime ordnance in the Baltic) in 2001.

RN CDs were again in action to clear the Shatt-al-Arab and Khawr abd Allah waterways into the port of Basra during Operation Telic, the war that deposed Saddam Hussein of Iraq. They remained in Iraq after the war to complete the clearance of Iraqi ports, conduct joint service EOD and search for weapons of mass destruction. Accounts of this activity can be found in the MCDOA website News Archives for 2003. They are currently serving with EOD and IEDD teams in Afghanistan.

Today, CD units remain busy around the country conducting explosive ordnance disposal, usually of wartime ordnance washed up on the beach or hauled up by fishing vessels, complex underwater engineering tasks on ships and submarines, search and recovery operations and many other tasks as well as providing Military Assistance to the Civil Powers (MACP) for such tasks as Improvised Explosive Device Disposal (IEDD) and Maritime Counter Terrorism (MCT). Clearance diving elements are also embarked in mine countermeasures vessels (MCMVs) as an integral part of the weapons system for mine disposal. Perhaps uniquely in the RN, members of the CD Branch perform their hazardous wartime role of dealing with live ordnance on a daily basis even in peacetime. Use these links to download information from the Royal Navy website about becoming a Warfare Officer (including Mine Clearance Diving Officer) or a Mine Clearance Diver Specialist Rating.

Find out more about modern Minesweepers, Mine Hunters, Diving Teams and ongoing operations here.

HMS Vernon and Royal Naval Reserve Diving after 1960

by Bob Baser

The Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) had eleven Divisions in the 1960s and 70s that operated minesweepers (and latterly two mine hunters) of 10th Mine Counter Measures Squadron with RNR crews. In addition to sea training in their local areas at weekends, the ships took part in major naval exercises. Crews would either use their holiday entitlement, or if employers allowed, take additional unpaid leave to man the ships. HMS Vernon hosted an annual training period (VERMEX) which tested and developed the crews in their full range of skills.

RNR Ship’s Diver using Swimmers Air Breathing Apparatus (1970s)

Most of the seagoing Divisions supported a team of RNR Ship’s Divers. To become a Ship’s Diver required successful completion of the Royal Navy (RN) Ship’s Diver course, held for ratings at HMS Drake and officers at HMS Vernon until 1980 when the training of ratings moved to HMS Vernon. These RN courses were of one month duration compared with the normal RNR training periods of two weeks. Personnel wishing to complete the course were reliant on the generosity of their civilian employers as civilian annual leave entitlement was still generally only two or three weeks at this time.

The RN Ship’s Diver qualification was an additional qualification and RNR ratings and officers (as did their RN equivalents) still had to carry out evening and weekend training and duties required by their parent Branches of the RNR while, additionally, carrying out the regular time underwater required to maintain competency.

The RNR diving teams were responsible for the maintenance of their own diving equipment. HMS Vernon provided the breathing apparatus maintenance training for RNR ratings who were trained civilian technicians (generally serving in the engineering branches).

In 1980 two RNR Ship’s Diver Officers completed the Royal Navy’s Long Mine Clearance Diving Officers course at HMS Vernon. This required commitments normally expected of full time RN Officers and only achievable by extended time away from civilian employment.

RNR Ship’s Diver using Diving Set Self-Contained Compressed Air (1980s)

The development potential for the RNR divers was recognised by the RN in the early 1980s. To facilitate this development, additional courses were provided at HMS Vernon for the RNR Ship’s Divers by the Chief Diver (Reserves) (CD(R)). These courses included tool training, afloat propeller changing for mine countermeasure vessels, explosive ordnance recognition (not demolition) and sea bed searches of ports and anchorages. Training often used the Horsea Lake facilities at Horsea Island. This increased activity was the precursor to the formation of a rating only Branch of the RNR, the Port Diver (PD). Most of the RNR Ship’s Divers transferred into this Branch.

PDs were required to complete the same minimum time underwater each year as a full-time clearance diver, double the time previously expected for Ship Divers. With the PD role expanding, officers were finally taken into the Branch. In addition to training in their home ports in the evenings and at weekends, teams of PDs took part in major exercises in the UK and overseas including combined activities with full time diving teams of other nations. The logistics, organisation, guidance and on-site support for these exercises was provided by a Staff Diving Officer (Reserves) and CD(R) based at HMS Nelson (Gunwharf) as HMS Vernon was known after 1987.

The Branch was expanded in 1990 to include RNR officers as Port Diver Officers and WRNR ratings. Two WRNR ratings subsequently completed their diving course at HMS Nelson (Gunwharf).

The Port Diving Branch was disbanded when the Government introduced ‘Options for Change’ in 1992. Ship’s Divers continued in service throughout the RN and RNR until 2006.

The 21st century has seen the re-establishment of an RNR Diving Branch with the roles expanding from those of the 20th century Port Diver.

Find out more about Royal Navy Diving via the links below:

The History of Royal Navy Diving

More RN mine warfare and diving stories.

Royal Navy Clearance Divers - Forces TV Item

What does it take to be a Royal Navy Clearance Diver?

Royal Navy Clearance Divers Association

Find out more about modern Minesweepers, Mine Hunters, Diving Teams and ongoing operations here.